Sweden’s strategy to keep large parts of society open is widely backed by the public. It has been devised by scientists and backed by government, and yet not all the country’s virologists are convinced.

There is no lockdown here. Photos have been shared around the world of bars with crammed outdoor seating and long queues for waterfront ice cream kiosks, and yet it is a myth that life here goes on “as normal”.

On the face of it little has shut down. But data suggests the vast majority of the population have taken to voluntary social distancing, which is the crux of Sweden’s strategy to slow the spread of the virus.

Usage of public transport has dropped significantly, large numbers are working from home, and most refrained from travelling over the Easter weekend. The government has also banned gatherings of more than 50 people and visits to elderly care homes.

Around 9 in 10 Swedes say they keep at least a metre away from people at least some of the time, up from seven in 10 a month ago, according to a major survey by polling firm Novus.

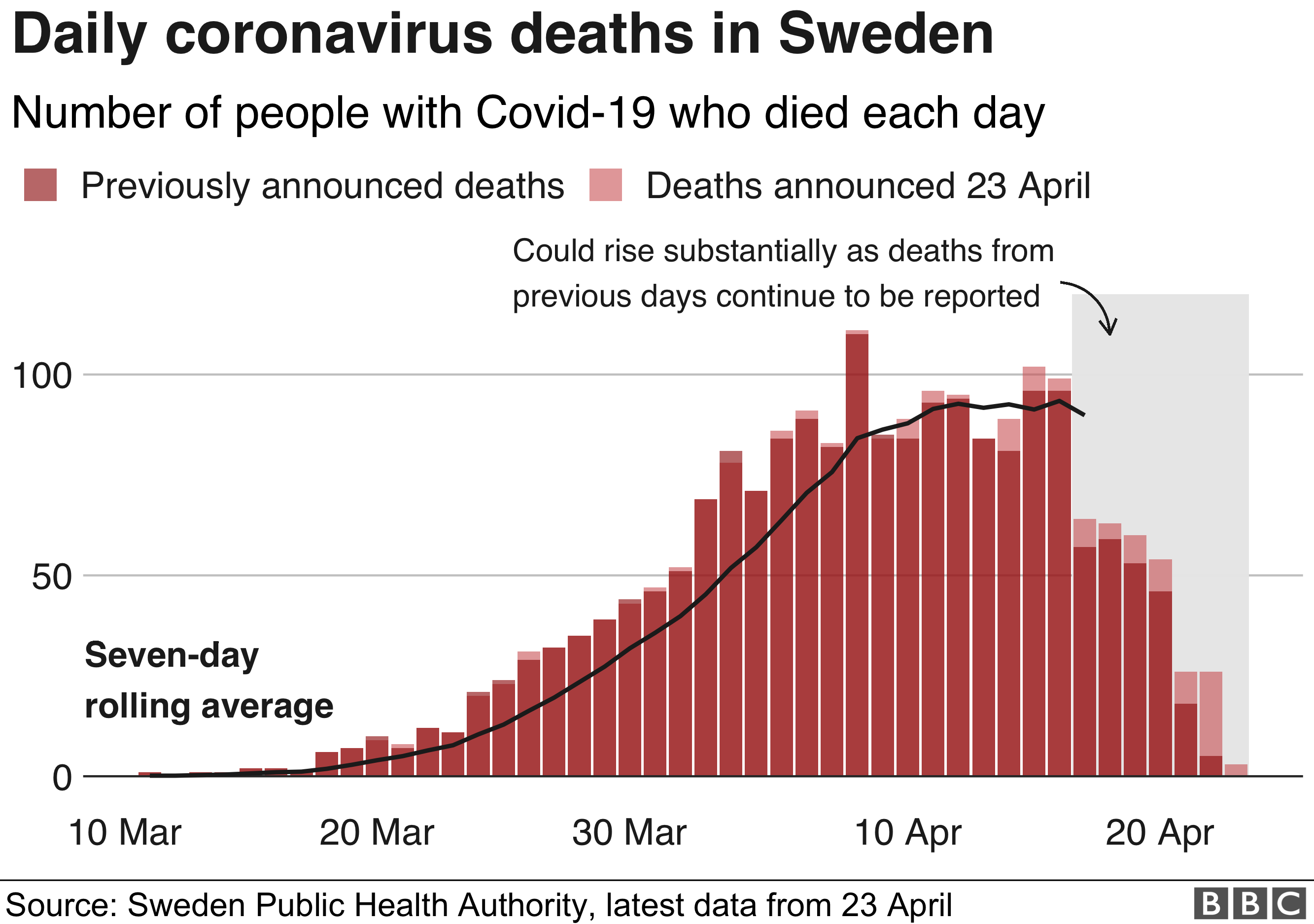

How serious is Sweden’s outbreak?

Viewed through the eyes of the Swedish Public Health Agency, the way people have responded is one to be celebrated, albeit cautiously.

The scientists’ approach has led to weeks of global debate over whether Sweden has adopted a sensible and sustainable plan, or unwittingly plunged its population into an experiment that is causing unnecessary fatalities, and could fail to keep the spread of Covid-19 under control.

In Stockholm, the epicentre of the virus so far, cases have largely plateaued, although there was a spike at the end of this week, put down partly to increased testing.

There is still space in intensive care units and a new field hospital at a former conference venue is yet to be used.

“To a great part, we have been able to achieve what we set out to achieve,” says state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell. “Swedish healthcare keeps on working, basically with a lot of stress, but not in a way that they turn patients away.”

In contrast with other countries where political leaders have fronted the national response to the crisis, Dr Tegnell has led the majority of news conferences.

His tone is typically matter of fact, with a strong focus on figures, and few mentions of the emotional impact of the crisis on victims and their families.

But the Swedish Public Health Agency has maintained high approval ratings throughout the pandemic.

Why Sweden chose a different path

Sweden’s decision to leave larger parts of society open than most of Europe came after Dr Tegnell’s team used simulations which anticipated a more limited impact of the virus in relation to population size than those made by other scientists, including those behind a major report by Imperial College, London.

That report apparently swayed the UK government to introduce a lockdown.

In addition, the Swedish Public Health Agency pushed the idea early on that a large proportion of cases were likely to be mild.

But it denied its strategy was based on the overall goal of herd immunity.

A core aim was to introduce less stringent social distancing measures that could be maintained over a long period time. Schools for under-16s have remained open to enable parents to keep working in key areas.

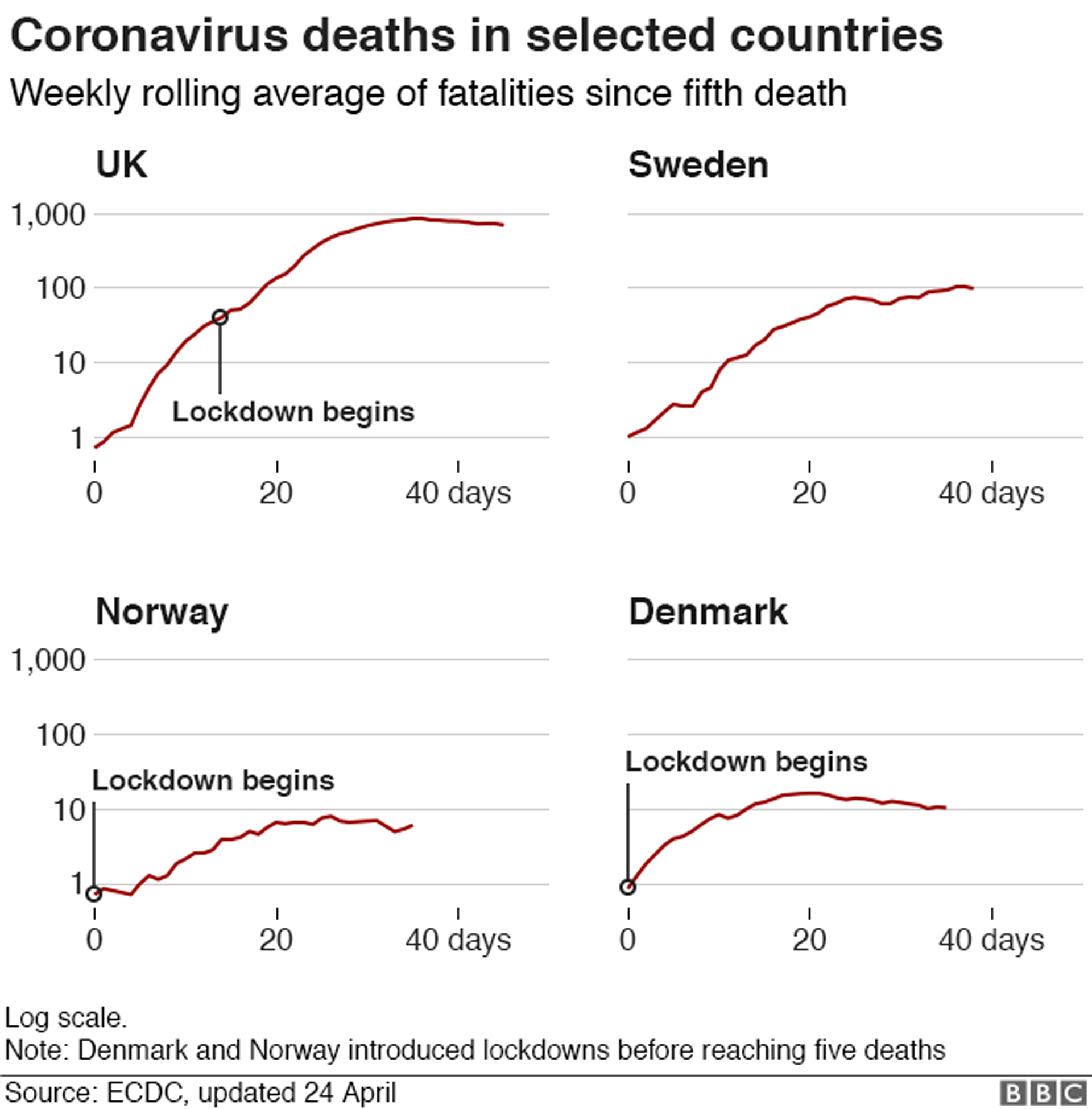

All other Nordic countries opted for stricter temporary restrictions, although some of these have since been relaxed.

What do the numbers tell us?

Sweden, with a population of 10 million, remains amongst the top 20 in the world when it comes to the total number of cases, even though it mostly only tests those with severe symptoms. More widespread checks on key workers are now being introduced.

It has higher death rates in relation to its population size than anywhere else in Scandinavia.

Unlike in some countries, Sweden’s statistics do include elderly care home residents, who account for around 50% of all deaths. Dr Tegnell admits that is a major concern.

Foreign residents, particularly those from Somalia who are more likely to live in multi-generational households, are also overrepresented in the figures.

“There are too many people dying,” says Claudia Hanson, an epidemiologist based at Karolinska Institutet, Sweden’s largest medical research facility. She is critical of the government’s approach and argues more of society should have been temporarily shut down in March while officials took stock of the situation.

Dr Hanson is among 22 scientists who wrote a damning piece in Sweden’s leading daily last week, suggesting “officials without talent” had been put in charge of decision-making.

The man leading Sweden’s response

But chief state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell is broadly popular in Sweden. An experienced scientist with more than 30 years in medicine, he is known for his relaxed demeanour and preference for pullovers.

“He’s a low-key person. I think people see him as a strong leader but not a very loud person, careful in what he’s saying,” reflects Emma Frans, a Swedish epidemiologist and science writer. “I think that’s very comforting for many.”

She argues that many national and international media have been “searching for conflict” within the scientific community, whereas she believes there is a consensus that Anders Tegnell’s approach is “quite positive”, or at least “not worse than other strategies”.

Will Swedes develop immunity?

History will judge which countries got it right. But the latest scientific discussion is focused on the number of Swedes who may have contracted the virus without showing any symptoms.

This is important because many scientists here believe Swedes may end up with much higher immunity levels compared with those living under stricter regulations.

A public health agency report this week suggested around a third of people in Stockholm will have been infected by the start of May.

That was later revised down to 26% after the agency admitted a calculation error. But several high-profile scientists have offered even greater numbers.

Prof Johan Giesecke, ex-chief scientist of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), believes at least half of all Stockholmers will have caught the virus by the end of the month.

It could even be up to half the population of Sweden, suggests Stockholm University mathematician Tom Britton.

Is this Swedish ‘exceptionalism’?

What happens next in Sweden may largely depend on people carrying on with social distancing.

Some Swedes have responded with an “outburst of nationalism” and a “sense of pride, for Sweden deviating from the European norm”, says Prof Nicolas Aylott, a political scientist at Stockholm’s Södertorn University.

“It sort of chimes with a rather deep seated sense of Sweden’s specialness.”

That may encourage some Swedes to follow the recommendations but the country is by no means united.

On social media there has been vocal dissent from some foreign residents championing tougher measures.

Meanwhile, there are signs that others living in Sweden believe the worst of the crisis is over.

Mobile phone data suggests Stockholm’s residents are spending more time in the city centre than a fortnight ago, and last weekend police raised concerns about overcrowding in nightlife hotspots.

Prime Minister Stefan Lofven has warned it is “not the time to relax” and start spending more time with friends and family.

But with spring weather arriving after Sweden’s notoriously long, dark winter, that may be easier said than done.