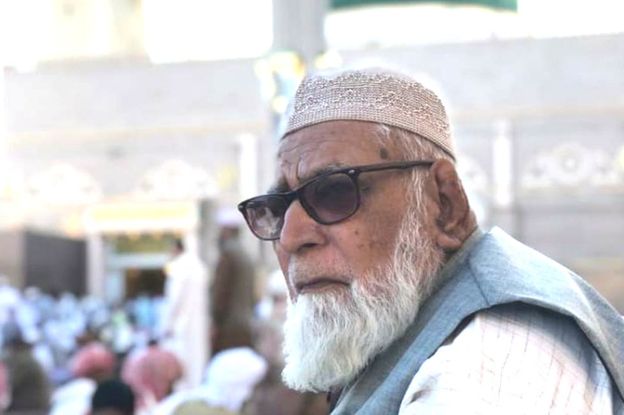

In his last pictures, Muhammad Husain Siddiqui, wearing a brimless cap and brown tunic, is peering into the camera.

It is the last day of February. Siddiqui has just returned to India after a month-long stay with his younger son, who works as a dentist in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

The 76-year-old Islamic scholar and judge looks visibly tired. Smiling wanly, he accepts a bouquet from the family driver outside the airport in the southern city of Hyderabad.

They get into their Chevrolet sedan, and head home to Gulbarga some 240km (150 miles) away in neighbouring Karnataka state. They take lunch and tea breaks and drive past forts and cotton farms in a journey that takes four hours.

“My father said he was fine. He looked good, having spent a month with my brother and his family. He asked about us,” his eldest son, Hamid Faisal Siddiqui, told me.

But 10 days later, his father was dead – India’s first official Covid-19 fatality.

He first began feeling sick a week after his return. He died three days later, gasping for air in a moving ambulance. Anxious family members had ferried him between two cities and four hospitals in less than two days. Rejected by four hospitals, he died on his way to the fifth, where he was declared “brought dead”.

The day after Siddiqui died, authorities announced that he had tested positive for the virus.

“We still do not believe he died of Covid-19. We haven’t even got the death certificate,” Ahmed Faisal Siddiqui told me.

In many ways, the story of his father’s death underlines the chaos and confusion often marring the treatment of Covid-19 patients in India.

Siddiqui was fine on his return to his two-storey home in Gulbarga, where he lived with his eldest son and his family.

He had given up working five years ago. His wife had died from cancer since then. His friends said he mainly spent his time in his well-appointed office room with its book-lined shelves. He was also the caretaker of the biggest local mosque. “He was a generous, erudite man,” said Ghulam Gouse, a friend.

He complained that he was feeling sick on the night of 7 March. He woke up early the next morning, coughing violently and asking for water.

The family doctor, a 63-year-old local physician, had arrived promptly, given him a tablet for a cold and gone away.

The cough worsened and that night he slept fitfully. Now, he also had a fever.

On the morning of 9 March, the family took Siddiqui to a private hospital in Gulbarga, where he spent 12 hours under observation.

Here is where the story gets confusing.

The discharge note from the private hospital provided to the family says Siddiqui was suffering from pneumonia in both lungs. The patient also suffered from hypertension, the examining doctor wrote. He referred him to a leading super-speciality hospital in Hyderabad for “further evaluation” – but did not mention a suspected Covid-19 infection.

However, a statement released after his death by India’s health ministry, says the hospital in Gulbarga “provisionally diagnosed” him as a “suspected Covid-19 patient”.

The statement also says a swab sample was taken from Siddiqui during his stay in the hospital and sent to the city of Bangalore, 570km (354 miles) away, to test for the virus.

It then put the blame on the patient’s family for moving him out from the Gulbarga hospital.

“Without waiting for the test results,” the statement said, “the attendees [of the patient] insisted [on taking him away] and the patient was discharged against medical advice and attendees took him to a private hospital in Hyderabad.”

“I don’t know why we are being blamed for this. If they told us to keep my father here, we would have taken him to the local government hospital. We went by what the private hospital told us and we have evidence of that,” Hamid Faisal Siddiqui said.

But senior district officials I spoke to maintained that they had asked the family to agree to move Siddiqui to a local government hospital which had a designated Covid-19 ward. “But the family members were adamant about taking him away,” an official said.

On the evening of 10 March, Siddiqui was wheeled out on a gurney and put into an ambulance where a paramedic gave him oxygen and hooked him up to an IV. His son, daughter and a son-in-law accompanied him.

They drove through the night and reached Hyderabad the next morning.

There they moved Siddiqui from one hospital to another seeking treatment.

A neurological clinic denied admission, and referred the patient to a government hospital in Hyderabad that had a designated Covid-19 ward. The family waited there an hour. “No doctor showed up, nobody turned up, so we moved again”, a family member said.

Siddiqui was slowly sinking in the sweltering ambulance.

They finally took him to the super-speciality hospital.

Doctors examined him for a couple of hours. They noted that the patient “had been coughing for two days, followed by shortness of breath for two days”. He had been given paracetamol, nebulised and was on IV fluids. They “advised admission for further evaluation”.

But, the hospital noted in its discharge note, that the “patient attendant was not willing for admission for further evaluation despite risks [to patient] being explained”.

Again, the family insists that was not quite true. They said the super-speciality hospital asked them to “take the patient back to the government hospital, have him tested there for coronavirus and come back”.

“We were so confused, we left the place and decided to return to Gulbarga,” a family member said.

When the ambulance returned to Gulbarga early next morning, Siddiqui had stopped breathing. After travelling more than 600km (372 miles) on the road, he had given up.

“From the day of onset of symptoms till his death, patient has not visited any government facility,” the official report on his death said.

The next day, his son says, they found out “from TV that my father had become India’s first coronavirus casualty”. In the afternoon, they buried him quietly in a family graveyard.

Since Siddiqui’s death, Gulbarga has reported more than 20 cases and two more deaths from Covid-19. Siddiqui’s 45-year-old daughter and the family doctor were among those who tested positive. (They have recovered.)

More than 1,240 people are under home and hospital isolation. A total of 1,616 samples had been tested by Monday morning.

“Give me some water, I am feeling thirsty. Take me home,” Siddiqui had told his son in the ambulance that fateful night.

His family returned home, but he didn’t make it.