The US has imposed tough new economic sanctions aimed at deterring foreign business activity with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s government.

The measures in the Caesar Act seek to compel the government to “halt its murderous attacks” on civilians and accept a peaceful political transition.

For the first time, Mr Assad’s wife Asma has been targeted personally.

But there are fears that the sanctions will make the plight of ordinary Syrians even more desperate.

The war-torn country is grappling with a worsening economic crisis.

Its currency has plummeted in value on the black market, sending prices of food and medicine soaring and prompting rare protests against President Bashar al-Assad in government-controlled areas.

More than 380,000 people have been killed and 11 million others have been displaced since an uprising against Mr Assad began in 2011.

Government forces have regained control of most of the country with the help of Russia’s military and Iran-backed militiamen.

However, rebels supported by Turkey and jihadists still hold areas in the north-west, while Kurdish-led fighters backed by the US control part of the north-east.

What do the sanctions target?

The US has imposed sanctions on Syria for decades, but they were extended in 2011 to press the government to end its bloody crackdown on opponents.

The Caesar Act, which was included in legislation passed in December, is named after a military photographer codenamed “Caesar” who came from Syria with 52,275 images of torture and death from inside government prisons.

It authorises “diplomatic and coercive economic means” to “compel the government of Bashar al-Assad to halt its murderous attacks on the Syrian people and to support a transition to a government in Syria that respects the rule of law, human rights, and peaceful co-existence with its neighbours”.

The act directs the president to impose sanctions on any foreign person:

Providing significant financial, material, or technological support to the Syrian government or to a foreign person operating in a military capacity inside Syria on behalf of the governments of Syria, Russia, or Iran

Selling or providing goods, services, technology or information that facilitates the Syrian government’s production of oil and gas; its purchases or maintenance of military aircraft; and its construction and engineering projects

Entering into contracts related to reconstruction in areas of Syria controlled by the Syrian government and its allies

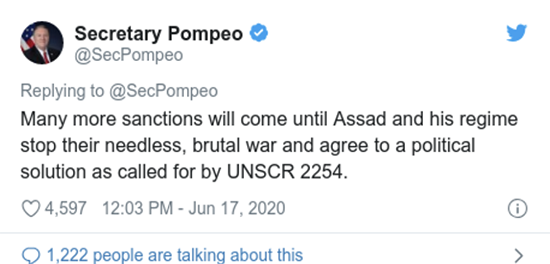

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced on Wednesday that sanctions would be imposed on 39 individuals and entities under the act.

“I will make special note of the designation for the first time of Asma al-Assad, the wife of Bashar al-Assad, who with the support of her husband and members of her Akhras family has become one of Syria’s most notorious war profiteers,” he said, without providing any evidence.

There was no immediate comment from Mrs Assad, a dual British-Syrian national who worked as an investment banker in London before getting married and now runs a major charity network in Syria.

She has defended the policies of her husband, who has repeatedly denied that his forces have committed atrocities and insisted that they are fighting terrorists.

Why could this hurt ordinary Syrians?

The problem is that Syria’s economy is already in meltdown. Syrians are going hungry in a way they were not even a year ago.

Economic sanctions are often a blunt instrument and many analysts fear the Caesar Act might miss its target. Instead, it could deliver a devastating blow to what remains of the Syrian economy after getting on for a decade of war.

The economic crisis over the border in Lebanon, particularly the collapse of the banks, has cut Syria’s main link to the outside world. The result is the real value of the Syrian currency has plummeted, putting the price of imported staple foods beyond the reach of most people.

As well as targeting the Assad regime, the Caesar Act also fits in with President Donald Trump’s policy of “maximum pressure” on Iran and its surrogates, including Hezbollah, which is the strongest military and political force in Lebanon.

The act’s critics argue that eagerness in Washington to punish Iran could end up delivering an even more desperate existence to Syrian civilians.

What has been the reaction?

A Syrian foreign ministry source told the state news agency, Sana, that the US sanctions violated international law and accused officials in Washington of behaving like a “gang”.

“The US administration talking about human rights in Syria exceeds the ugliest forms of lies and hypocrisy as embodied in its policy of supporting terrorism that shed the blood of the Syrians and destroyed their achievements,” the source added.

At a virtual session of the UN Security Council on Tuesday, Russian permanent representative Vassily Nebenzi also criticised the sanctions, saying the US had confirmed “that the purpose of these measures is to overthrow the legitimate authorities in Syria”.

Zhang Jun of China warned that “as vulnerable countries like Syria are struggling with the [coronavirus] pandemic, imposing more sanctions is simply inhumane”.

[b][size=5]Путешествуй в мир киномагии с [url=https://hdkinofan.lol/]hdkinofan.lol[/url] – где каждый фрейм – это новое открытие![/size][/b]

Привет, киноманы и ценители искусства!

[b][size=4]Платформа hdkinofan.lol[/size][/b] приглашает вас в захватывающий мир кинематографа, где каждый фрейм наполнен волнующей интригой и невероятными сюжетами. ??

[b][size=3]Почему выбирают hdkinofan.lol?[/size][/b]

1. [b]Богатая библиотека фильмов:[/b] Наша коллекция фильмов впечатлит даже самого искушенного киномана.

2. [b]Высокое качество воспроизведения:[/b] У нас только качественное воспроизведение для настоящих ценителей кинематографа.

3. [b]Удобный интерфейс:[/b] Мы заботимся о вашем удобстве – наш интерфейс легок в освоении для всех пользователей.

[b][size=3]Почему именно hdkinofan.lol для настоящих кинолюбителей?[/size][/b]

Наш онлайн-кинотеатр – это место, где каждый найдет что-то по душе.

[b][size=3]Как начать погружение в киноинтригу?[/size][/b]

1. [b]Зарегистрируйся:[/b] Стань частью нашего кинематографического сообщества, регистрируйся и получай доступ к увлекательным фильмам.

2. [b]Выбери фильм:[/b] Ознакомься с нашим каталогом и выбери фильм по своему настроению.

3. [b]Погрузись в киномир:[/b] Не просто смотри, а погружайся в мир киноинтриги с NewLordFilm.online!

Не упусти свой шанс создать собственный киноплейлист вместе с [b][url=https://hdkinofan.lol/]hdkinofan.lol [/url][/b]!

[b][size=3]Выбирай качественное кино с https://hdkinofan.lol/ – твой путь в мир бескрайних киновозможностей![/b]