Originally from France, Thibault Fornier, 55, and his business partner Jean Koala, 28, have spent the last 10 years building a “Tudor” castle, complete with turrets and battlements, on the outskirts of Burkina Faso’s capital, Ouagadougou.

Hamerkop Manor is loosely based on Hampton Court Palace, Henry VIII’s residence, on the outskirts of London.

Pouring tea from a Victorian-style tea set as he explains why he built it, Mr Fournier says: “I love the royal family, not all of them, but I love the Queen.

“I see her as the guardian of Western civilisation. I am convinced that after the Queen is gone, Western civilisation will disappear with her.”

Mr Fornier became enamoured with all things British after he went to the UK on a language exchange programme at the age of 15.

“I like the English lifestyle – English cars, architecture. I even bought a Rolls Royce the same day I bought this land,” he says.

Since moving to West Africa in the 1980s he has worked in the creative side of advertising in three former French colonies – Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast and Senegal – and has put much of the money he earned from it into the construction of Hamerkop, which is always continuing, he says.

In one corner of the garden, workers from the local village have constructed an enclosure for pet tortoises and are in the process of building a replica of London’s famous Tower Bridge, from which the tortoises can be viewed.

The Windsors club

Mr Koala, a Burkinabé, became Mr Fornier’s business partner in 2012 after he started working as a labourer on the construction of Hamerkop.

“For the building of the castle, I had a hand in almost everything,” Mr Koala says.

“I was the supervisor and the site manager. Now that the main part of the building is built, I am head chef and manage the bar,” he adds.

Mr Koala has played a major role in turning Hamerkop into a business. To help cover the costs of the ongoing building work, it is now run as a private members’ club called “The Windsors”.

As head chef, Mr Koala serves seven course meals to guests, although he has opted for a French menu, rather than British.

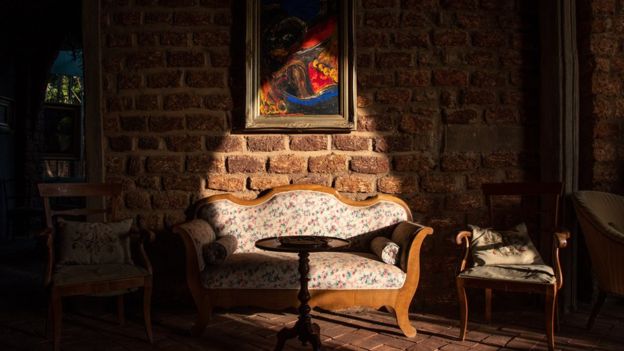

Almost every other aspect of Hamerkop has a distinctly British flavour – like the 12m (39ft) castle turrets and a thatched Tudor cottage. There are smaller pieces of memorabilia too.

On the window sill in the kitchen, is a sealed jar of commemorative marmalade from Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer’s wedding. Paintings and sketches of various members of the royal Windsor family can be found peppered across walls in many of the rooms.

Much of the furniture is imported from Europe and has a distinctly British feel to it.

A life-size metal sculpture of a stag, made by a Burkinabé artist, stands in the hallway greeting guests.

Six things about Burkina Faso:

A former French colony, it gained independence as Upper Volta in 1960

Capt Thomas Sankara seized power in 1983 and adopted radical left-wing policies – he is often referred to as “Africa’s Che Guevara”

The anti-imperialist revolutionary renamed the country Burkina Faso, which translates as “land of honest men”

People in Burkina Faso, known as Burkinabés, love riding motor scooters

It is renowned for its pan-African film festival, Fespaco, held every two years in Ouagadougou

The cotton-exporting nation is battling an Islamist insurgency in the north.

There are also symbols of mortality and death throughout Hamerkop. There is a small chapel filled with Catholic icons, which Mr Fornier says was made to commemorate loved ones who have passed away, especially his mother.

Above the fireplace in the living room, hangs a reproduction of Arnold Böcklin’s painting Isle of the Dead.

On the window sill is a statuette of the crucifixion surrounded by items traditionally associated with witchcraft in Burkina Faso – the hand of a monkey, a tortoise shell and porcupine spikes, propped up inside bell jars.

“I am trying to show the link between religions here. Because someone has faith in the hand of a monkey, we call him an animist. For me, all religions are the same. We all believe in a superior being,” Mr Fornier says.

“I am a Christian, but I’m especially fascinated by [Catholic] burial ceremonies,” he adds.

‘Gilded cage’

Some visitors suggest that Hamerkop can feel like an uncomfortable throwback to a colonial era, but Mr Fournier points out that he is well integrated with those living in the local village.

“I eat and drink with them. I behave as a villager here,” he says.

When asked about the future of Hamerkop, he replies: “I can’t do anything else except continue.

“If someone comes to buy this place for 500m francs ($827,400; £669,000), we can sell it, but what will we do with the money?

“We would just start building again… It’s a gilded cage. We are doomed to continue.”

He says that after he is gone, his business partner and his children will be unlikely to continue running Hamerkop.

“I think [it] will crumble, but people will still visit in 30 or 50 years.

“They’ll see the ruins and think – some kind of madness existed here once.”